For Native American Women in Alaska, Scourge of Rape, Rare Justice

May 24, 2012

The New York Times – Alaska — She was 19, a young Alaska Native woman in this icebound fishing village of 800 in the Yukon River delta, when an intruder broke into her home and raped her. The man left. Shaking, the woman called the tribal police, a force of three. It was late at night. No one answered. She left a message on the department’s voice mail system. Her call was never returned. She was left to recover on her own.

The New York Times – Alaska — She was 19, a young Alaska Native woman in this icebound fishing village of 800 in the Yukon River delta, when an intruder broke into her home and raped her. The man left. Shaking, the woman called the tribal police, a force of three. It was late at night. No one answered. She left a message on the department’s voice mail system. Her call was never returned. She was left to recover on her own.

“I drank a lot,” she said this spring, three years later. “You get to a certain point, it hits a wall.”

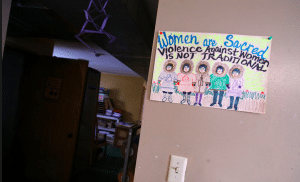

One in three American Indian women have been raped or have experienced an attempted rape, according to the Justice Department. Their rate of sexual assault is more than twice the national average. And no place, women’s advocates say, is more dangerous than Alaska’s isolated villages, where there are no roads in or out, and where people are further cut off by undependable telephone, electrical and Internet service.

The issue of sexual assaults on American Indian women has become one of the major sources of discord in the current debate between the White House and the House of Representatives over the latest reauthorization of the landmark Violence Against Women Act of 1994.

A Senate version, passed with broad bipartisan support, would grant new powers to tribal courts to prosecute non-Indians suspected of sexually assaulting their Indian spouses or domestic partners. But House Republicans, and some Senate Republicans, oppose the provision as a dangerous expansion of the tribal courts’ authority, and it was excluded from the version that the House passed last Wednesday. The House and Senate are seeking to negotiate a compromise.

Here in Emmonak, the overmatched police have failed to keep statistics related to rape. A national study mandated by Congress in 2004 to examine the extent of sexual violence on tribal lands remains unfinished because, the Justice Department says, the $2 million allocation is insufficient.

But according a survey by the Alaska Federation of Natives, the rate of sexual violence in rural villages like Emmonak is as much as 12 times the national rate. And interviews with Native American women here and across the nation’s tribal reservations suggest an even grimmer reality: They say few, if any, female relatives or close friends have escaped sexual violence.

“We should never have a woman come into the office saying, ‘I need to learn more about Plan B for when my daughter gets raped,’ ” said Charon Asetoyer, a women’s health advocate on the Yankton Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, referring to the morning-after pill. “That’s what’s so frightening — that it’s more expected than unexpected. It has become a norm for young women.”

To read the New York Times article, click here.