Five Myths About Title IX

April 20, 2012

ESPNW- Title IX is so veiled in mythology that whole sections of websites exist to debunk falsehoods about what the statute can and cannot do.

ESPNW- Title IX is so veiled in mythology that whole sections of websites exist to debunk falsehoods about what the statute can and cannot do.

Throughout the years, the NCAA has released numerous studies analyzing Title IX. The NCAA also maintains a quick-hit FAQ page on its website that delivers important facts, including what might be the most important detail of all: Since the law’s inception, both male and female participation in college sports has increased.

“Title IX is only powerful for women if there are strong men’s programs and vice versa,” says Nancy Hogshead-Makar, a former Olympic swimmer and current professor at Florida Coastal School of Law.

Even so, the 40th anniversary of Title IX is sure to revive a number of old falsehoods — and probably inspire some new ones. A recent article in The Atlanticblamed Title IX for ACL injuries, eating disorders and sexual abuse by coaches, to name a few. But as experts point out, nearly all the horrors cited happened outside of school settings; the problems had nothing to do with education, which is what Title IX actually covers.

Clearly, there is no shortage of opinions. So espnW spoke with coaches, administrators and researchers about the facts. Here, with help from two of the most pre-eminent experts on Title IX — Hogshead-Makar and Karen Morrison, the NCAA’s director of gender initiatives — we examine five prevalent myths.

Myth No. 1: Title IX is controversial

“I’d say that is the biggest myth out there,” says Hogshead-Makar, who is also senior director of advocacy for the Women’s Sports Foundation. Citing three major polls, including one by The Wall Street Journal and CNN, she notes that about 80 percent of people surveyed say they want Title IX left alone or strengthened. “There’s a very small group of noisy people opposed to Title IX,” she says. “The vast majority of the public wants men and women to have equal educational opportunity, including in athletics.”

While Title IX is viewed favorably by the general public, it often sparks loud debate within the sports world, which is where a lot of those “noisy people” reside. Often, they are athletes or supporters of small-budget men’s programs that have been cut — people who feel they’ve lost opportunities of their own. Their frustration is understandable. Unfortunately, it is also misplaced, according to experts who have studied the numbers. John Cheslock, an associate professor at Penn State, addressed this issue in a 2008 report on the effects of Title IX in intercollegiate athletics, writing, “If you get some statisticians in the room, they can pretty quickly show that, well no, there haven’t been these large declines in men’s participation.”

And yet the myth persists. Hogshead-Makar and Morrison call this a classic case of pitting the “have-nots” (women’s sports and small-budget men’s sports) against each other rather than taking a cold, hard look at the “haves” (big-budget football and men’s basketball). The Women’s Sports Foundation has issued an easy-to-digest Title IX mission statement that addresses this issue head on.

Myth No. 2: Title IX forces schools to cut men’s sports

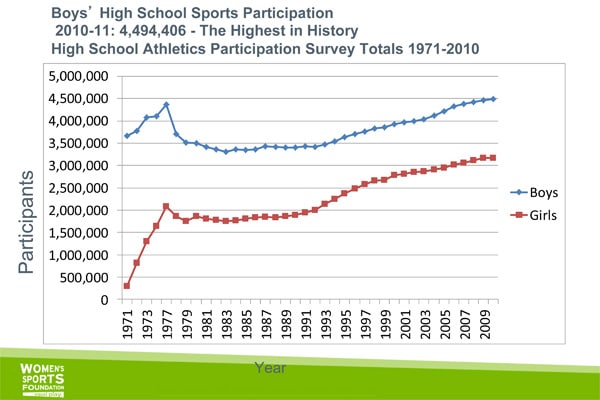

When women’s sports opportunities rise, so do men’s. Hogshead-Makar has a favorite chart to illustrate this point. If men’s sports were being dropped at the expense of women’s sports, she says, “What you’d see is the two curves coming together — but that doesn’t happen.”

Women’s Sports FoundationBoys still have more opportunities than girls in the Title IX era.

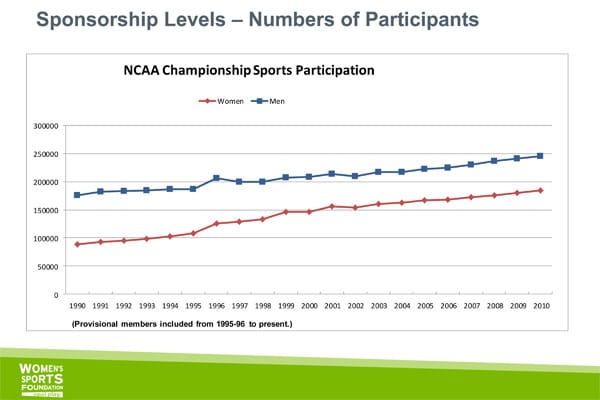

Women’s Sports FoundationBoys still have more opportunities than girls in the Title IX era.Since 1988-89, the NCAA has added 510 men’s teams. According to data released by the NCAA in 2011, the number of male student-athletes has grown from 214,464 in 2002 to 252,946 in 2011. That’s an increase of 38,482. During that same period, the number of female student-athletes increased from 158,469 to 191,131, a gain of 32,662.

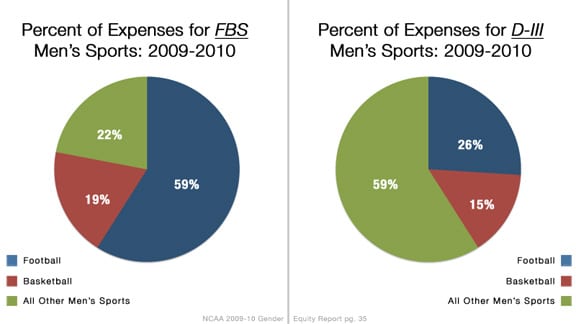

So what causes non-revenue sports to be dropped? King football and prince basketball. Football and hoops programs constitute 78 percent of men’s sports budgets in Division I’s Football Bowl Subdivision. In Division III, those sports take up just 41 percent of men’s costs. Put another way, the need to spend money to stay in the big time crowds out other sports. But over the years, as Hogshead and others point out, administrators have found it more convenient to blame Title IX than football or men’s basketball for cuts to non-revenue men’s programs.

Schools must decide where to spend their money. And often, when they decide to cut non-revenue men’s sports — such as wrestling, swimming and tennis — it’s not so they can fund women’s sports, but rather so they can pump more money into football. In 2006, Rutgers University decided to cut men’s tennis, which had a budget of approximately $175,000. That same year, as The National Women’s Law Center points out, Rutgers spent approximately $175,000 on hotel rooms for its football team — for home games.

NCAAFootball rules the day in Division I, often at the expense of non-revenue men’s sports.

NCAAFootball rules the day in Division I, often at the expense of non-revenue men’s sports.Morrison shares another data point pertaining to college wrestling, often portrayed as the biggest victim of

Title IX. In 1984, the Supreme Court held in Grove City v. Bell that only institutions or programs receiving direct federal government financial assistance had to comply with Title IX, which “placed college athletics beyond the reach of Title IX because athletic departments hardly ever received federal financial funds,” writes Vermont Law School professor Brian L. Porto in his book “A New Season: Using Title IX to Reform College Sports.”

The decision was rendered moot in 1988 when Congress overrode President Ronald Reagan’s veto of the Civil Rights Restoration Act, which forced any institution receiving federal funds to comply with Title IX throughout the entire institution.

During that four-year span when Title IX was not in effect for athletic departments, NCAA schools still dropped 53 wrestling programs, an average of 13.2 a year. From 1988 to 2000, when the law again covered sports, wrestling cuts slowed dramatically, with 56 programs dropped during that 12-year period, an average of

4.7 a year.

Myth No. 3: Opportunities are now equal

“That’s not true in intercollegiate athletics,” Morrison says.

Although the number of female athletes has skyrocketed since Title IX’s inception, the data show that a disturbing gap still exists in participation and funding. Twenty years after Title IX was passed, the NCAA commissioned aGender Equity Task Force, which released some eye-opening numbers. Men made up 69.5 percent of intercollegiate athletes and their programs used 70 percent of the scholarship funds, 77 percent of the operating budgets and 83 percent of the recruiting budgets. As recently as 2004-05, females made up 55.8 percent of the undergraduate enrollment but only 41.7 percent of the athletes.

The NCAA has made strides, but as Morrison points out, “We’re still not there yet.” At the college level, female athletes still receive 86,000 fewer opportunities than men and $148 million less in athletic scholarships.

Women’s Sports FoundationMale and female participation in college sports continues to rise.

Women’s Sports FoundationMale and female participation in college sports continues to rise.Title IX hasn’t finished its job in high schools either. “Look at the difference in numbers: 1.3 million more boys than girls,” says Hogshead-Makar. Most schools give boys and girls the same number of teams but not the same number of opportunities per team. “So if you have boys’ sports like football and baseball, with lots of numbers, and you compare them with girls’ sports like golf and tennis, that’s where you get the big gaps. If you’re going to have football, you need to have three more girls’ sports in order to give girls the same opportunities.”

Myth No. 4: Schools must spend equally on men’s and women’s sports

There is nothing in the language of Title IX that demands equal spending. And few athletic departments spend equally. Almost universally, they spend more on men’s programs. A Women’s Sports Foundation study found female college athletes received only 35 percent of total athletic expenditures as recently as the 2004-05 school year.

The law allows for a school to spend differently on sports, but those differences can’t be discriminatory. If a college has football, men’s lacrosse and baseball, those sports are much more expensive to run and outfit. “And that’s OK, because there are reasonable differences in sports,” Morrison says. “But if you’re outfitting your women’s programs in substandard equipment, that would not be OK.”

The truth is that women’s sports still has a small piece of the pie. The NCAA Division I Athletics Programs Report contains detailed financial information for all Division I schools; on Page 23, it shows that in 2010, FBS Division I schools spent a median amount of $20,416,000 on men’s programs and $8,006,000 on women’s.

Myth No. 5: Men’s programs make money; women’s programs lose money

Nope, the whole enterprise resides primarily in the red.

Fewer than 7 percent of Division I sports programs operate in the black, according to an NCAA study published in 2010. Even big-time football and men’s basketball, sports generally assumed to operate at a profit, struggle to break even. That same NCAA study shows that only about half of FBS football and basketball programs generate enough revenue to cover their expenses.

Even that number is deceiving, says Hogshead-Makar, because “that excludes any capital expenditures or repayment on debt.” Throw in tax-exempt bonds that build the stadiums, weight rooms and tutoring centers, plus the tax-deductible booster donations that fund powerhouse programs, and those government subsidies make big-time football and basketball look like anything but a capitalist system.

Which is kind of the idea. Scholastic sports don’t exist to make money. Big programs need the NCAA infrastructure — with its tax breaks, institutional supports and free athletic talent — just as much as minor sports need big-program revenues. College football wouldn’t exist without women’s sports, because those schools wouldn’t be in compliance with Title IX.

“We start forgetting that it’s part of higher education, which is why it’s subject to Title IX,” Morrison says. “The whole point of this is that these programs are a piece of the educational system.”

And from an educational perspective, women’s sports more than hold up their end.

“There is almost no other group of students that graduates at the rates of female athletes,” Hogshead-Makar says. “They’re at something like 89 percent. They’re doing really, really well.”

Click here to read more.